Sometimes the best use of scripture is to change the wording. You can call this either misquoting or adapting. It is what the New Testament apostle Paul teaches me.

If this post has rubbed your hermeneutics the wrong way, please read on. Without quibbling over small points, I provide two of the best examples of changing the scriptures, both from Paul.

He provides the low hanging fruit, and his critics are the best source of guidance. As one writer puts it:

Almost stealthily, Paul makes the error of misquoting scripture and magically creates theology out of thin air. . . . His methodology with actually quoting scripture is similar to his interpretation of it: he will use or twist any scripture any way he chooses to prove his point!

. . . Paul Twists the Scriptures and Creates Theology out of Thin Air. . .

The writer, James Wood, goes on to illustrate his point, using the King James translation. The choice of translation shows his fairness. Wood refuses to scratch around for an arcane translation to support his point. He plays clean, as the soccer commentator may say.

He first quotes Paul. “And so all Israel shall be saved: as it is written, There shall come out of Sion the Deliverer, and shall turn away ungodliness from Jacob” (Romans 11:26). Paul’s point is clear: Jesus will come to save his people, “Jacob” being a figure of speech that represents the entire nation of Israel.[1]

Next James Wood quotes the original. “And the Redeemer shall come to Zion, and unto them that turn from transgression in Jacob, saith the Lord” (Isaiah 59:20). The difference is clear. Paul assigns redemptive agency to Jesus, while Isaiah assigns agency to Zion who usher in the messiah through their repentance. In Wood’s words, “Paul makes the deliverer turn away ungodliness instead of coming to those who themselves turned from transgression.”[2]

One could dismiss the difference as being two sides of one coin: grace on God’s side must be invited by repentance on the human side. But I prefer to run with Wood on this and agree heartily that Paul deliberately misquoted the scripture. It’s consistent with Paul’s entire mission, to show the Old Testament law fails precisely where the New Testament grace succeeds. Put differently, that the things humans fail to do to reach God were performed by Jesus and are offered as a gift by faith, no strings attached.

The second example comes from Deuteronomy 30:11-14 and Romans 10:6-10.[3] The entire chapter of Deuteronomy is encouraging, stating that following God’s commands “not too difficult for you or beyond your reach,” with the result that his people may receive blessings and not curses. However, the emphasis remains upon doing—and that often involves self-reliance instead of the intended reliance upon God, our Maker.

Hundreds of years later, Paul, who was an expert at taking the letter of the law with all seriousness and commitment, realized his devotion to God’s commands was making him a monster (also known as chief of sinners). He realized his obedience was…

- not sufficient

- resulted in garbage (including approving of the murder of Stephen)

- could never produce divine results, and

- was surpassed by the righteousness that came by faith, not willpower

(Philippians 3:7-9)

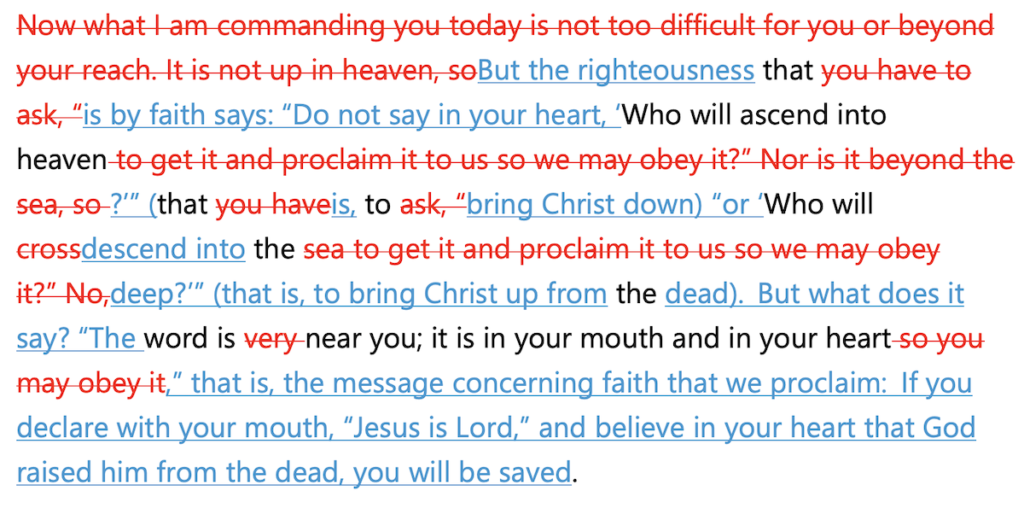

A few years after writing to the Philippians, Paul writes to the Romans. He re-reads Deuteronomy from the perspective of one who no longer trusts in human effort—at all. What he retains is the statement that “the word is very near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart….” Paul, however, changes the end of the statement. Where Moses writes “so you may obey it,” Paul writes, “that is, the message concerning faith that we proclaim.” He deliberately replaces obedience with faith.[4 see illustration]

The replacement is consistent with his entire treatment of the passage from Deuteronomy. Where Moses says obedience is not “beyond your reach,” Paul says that declaring with your mouth and believing in your heart are sufficient.

Paul also adds a cosmic dimension to Moses, who wanted to express that the Israelites had “the command” right at hand, and that they did not need to go to heaven nor across the sea to get the command. Paul agrees that the believer need not go to heaven, but he adds that such an act would bring Christ back down to earth, as if one visit to earth were not enough. He then changes “the sea” to “the deep” (or “the abyss”) with echoes of hell, claiming that such an effort would, again, bring Christ up from the dead. Instead, he concludes that confessing and believing in what Christ has already done are all that is required.

As Paul writes elsewhere: “Even to this day when Moses is read, a veil covers their hearts. But whenever anyone turns to the Lord, the veil is taken away. Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Corinthians 3:15-17). People can repent all day long and live with guilt all their lives. But when they see the perfect and complete forgiveness of Jesus, the veil is removed and the emphasis shifts from what we do to what Christ has already done.

Many Bible teachers in Christ’s time and in our day put the letter of the law over the spirit of the law. Paul never felt bound to the letter for the letter’s sake. His commitment was “not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (2 Corinthians 3:6).

Thus, Paul recognized that words only approximate the truth. He expressed a similar thing elsewhere saying that we see through a mirror only dimly.

Yes, we are treading on thin ice here, knowing that such interpretive license gives rise to cults and contortions of the scriptures. But that’s the cost of revelation. By definition it is not understood from the beginning. It is hinted at, alluded to, and, finally, in the life of Christ, made as visible as humans are capable of seeing. The key isn’t, “does this fit the letter of the law?” but “does this fit the one who forgave, healed, inspired, and commissioned all those who sought his help?”

The question is, “do you want the security of religion or the joy of revelation?” The first path is safe and may or may not lead you to your destination. Remember, Jesus called the Bible scholars of his day “blind guides.” The second path offers us glimpses of a love and goodness that outshines the dark reflections with which we usually live.

§ Footnotes §

[1] Using the part (Jacob) for the whole (Jewish nation) is synecdoche, a common figure of speech. We use it every time we refer to “Washington” for the United States federal government.

[2] Wood’s quote continues in a disparaging manner, true to his theme: “Such simple changes could fool the Gentiles that Paul was so devoted to saving. Instead of Paul becoming a contemporary Jonah and instructing the sinners to repent, Paul offers deceit and lies. Maybe this explains this verse that came from Paul’s pen.”

[3] Credit for this example to James Barron, who has his own grace-imbued website.

[4]