This is what Matthew writes:

“He took up our infirmities

and bore our diseases.”

. . . Matthew 8:17. . .

The “he” refers to the Jewish “suffering servant” whom Christians univocally interpret as Jesus of Nazareth. The claim is stunning. As Matthew quotes the passage, Jesus has taken away our sicknesses, just as he has taken away our sin. Whether it was the scourging or the crucifixion, the suffering Christ carried away our sickness.

When I first noticed the passage in Matthew, I thought he had mistranslated the Hebrew. The reason I thought that is because nearly every available English translation quotes Isaiah 53:4 in approximately the following way:

Surely he took up our pain

and bore our suffering,

yet we considered him punished by God,

stricken by him, and afflicted.

But he was pierced for our transgressions,

he was crushed for our iniquities;

the punishment that brought us peace was on him,

and by his wounds we are healed.

. . . Isaiah 53:4-5, NIV. . .

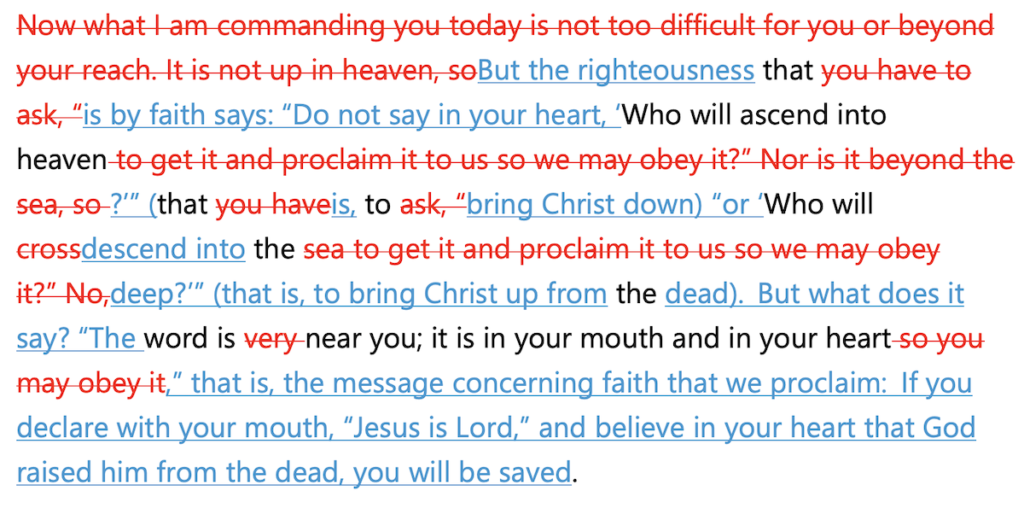

Where Matthew specifies physical “infirmities” and “diseases,” most translations offer emotional “pain” and “suffering.”[1]

Matthew, however wasn’t reading English translations. He also wasn’t depending on the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament that the Apostle Paul relied on. Matthew was following the original Hebrew. And it fit the context perfectly. The entire passage where Isaiah 53:4 is quoted demonstrates Jesus’ business of healing the physically and mentally ill:

When Jesus came into Peter’s house, he saw Peter’s mother-in-law lying in bed with a fever. He touched her hand and the fever left her, and she got up and began to wait on him.

When evening came, many who were demon-possessed were brought to him, and he drove out the spirits with a word and healed all the sick. This was to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah:

“He took up our infirmities

and bore our diseases.”

. . . Matthew 8:14-17. . .

Matthew, then, becomes the support for those who claim that both our salvation and our healing were accomplished by the sufferings of Jesus. The counter-argument is, of course, “I still feel sick,” but that is no different from “I still feel guilty,” or “I still sin.” The battle may be won on the cosmic scale but require tenacious insistence in every local instance. Long after World War 2 was won, outposts of Japanese soldiers were bearing arms and defending their ground, not knowing peace had been declared.

For those of us still reading, we can conclude with the apostle Peter. He does not misquote Isaiah 53:5, but he changes the tense to the present perfect, so suggest a past event has present effects. He reinforces the revelation that the whole-person redemption of Jesus is clearly a done deal:

“He himself bore our sins” in his body on the cross, so that we might die to sins and live for righteousness; “by his wounds you have been healed.” . . . 1 Peter 2:24. . .

The beauty of Peter’s version is that the common “if it is God’s will” falls completely to the wayside. Whether physical or spiritual healing is at hand, both are clearly God’s will, having been enacted in the suffering servant. No longer is it a matter of pulling out the divining rod to determine if these things are God’s will (the divining rod being a figure of speech for all the rationalizations we make). It is a matter of walking by faith, not by sight. It is a matter of trusting that the same Father who sent Jesus to redeem is the same Father who is completely aware of, and prepared for our current needs. That is true divine provision, also known as providence.

§ Footnotes §

[1] Of fifteen versions I checked, only New American Standard, Common English Version, and Young’s Literal Translation refer to sickness in Isaiah 53:4.

The versions that (mis)translate the Hebrew for sickness (חֳלָיֵנוּ) as “pain” or “suffering” include

- Amplified Bible

- American Standard (but has a footnote that provides “sickness” as an alternate word for “pain”)

- Common English Version

- English Standard Version

- Good News Translation

- King James Version

- Living Bible

- The Message

- New American Bible (Revised Edition)

- New Catholic Bible (uses “afflictions” which might be construed as “sickness”)

- New International Version

- Revised Standard Version (but has a footnote that provides “sickness” as an alternate word for “pain”)